Home » Posts tagged 'Remote work'

Tag Archives: Remote work

Peer Review at CHIWORK25

by Shiping Chen

Summer has brought not only sunshine but also the excitement of the annual CHIWORK conference! I’m thrilled to be a paper presenter at CHIWORK this year. CHIWORK 2025 is being hosted in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Although I wasn’t able to attend in person due to other commitments, I still felt the vibrant academic energy of CHIWORK as an online presenter.

My presentation was scheduled on the morning of 24 June, in the “AI IN HIGH-STAKES AND INSTITUTIONAL WORK” session. As a hybrid conference, CHIWORK provided a seamless and well-coordinated experience, making it easy for both in-person and online participants to engage with the programme. I really appreciated how smooth the transition was between talks, with Zoom rooms and Slack channels well-organised for announcements and Q&A.

My paper, Envisioning the Future of Peer Review: Investigating LLM-Assisted Reviewing Using ChatGPT as a Case Study, co-authored with my supervisors Prof. Duncan Brumby and Prof. Anna Cox, explores how Large Language Models like ChatGPT can support human reviewers during the peer review process. Rather than treating AI as a standalone reviewer, our study takes a human–AI collaboration perspective to understand how reviewers actually use ChatGPT in practice. We conducted a within-subject experiment with 24 HCI reviewers, each completing two review tasks—one with ChatGPT assistance and one without—followed by post-task questionnaires and interviews. Our findings show that ChatGPT can significantly reduce the perceived workload in drafting reviews and making judgments, and reviewers appreciated its support for summarisation, information retrieval, idea generation, and confidence-building. However, it did not lead to substantial time savings or improvements in review quality. These insights contribute to ongoing discussions around responsible AI integration in scholarly publishing and offer design implications for future peer review tools that complement human expertise.

The Q&A after my presentation gave me the opportunity to respond to insightful questions from the audience that touched on the core motivations and assumptions behind our study. It was a valuable chance to elaborate on the reasoning behind our experimental design, particularly why we chose to focus on ChatGPT as a case study. I was encouraged by the genuine interest in the practical implications of LLMs for real-world peer review, and the discussion helped me further reflect on how such tools might be responsibly integrated into academic workflows.

Although I joined the conference remotely, I still came away with a great deal of inspiration, thoughtful questions, generous feedback, and new ideas to take forward. I’m grateful to have been part of such a welcoming and intellectually engaging community, and I look forward to staying connected with CHIWORK in the years to come.

“Sometimes It’s Like Putting the Track in Front of the Rushing Train”: Having to Be ‘On Call’for Work Limits the Temporal Flexibility of Crowdworkers

Lascău, L., Brumby, D. P., Gould, S. J., & Cox, A. L. (2024). “Sometimes It’s Like Putting the Track in Front of the Rushing Train”: Having to Be ‘On Call’for Work Limits the Temporal Flexibility of Crowdworkers. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 31(2), 1-45.

This paper examines how the design of crowdsourcing platforms impacts the temporal flexibility of crowdworkers. We argue that being ‘on call’ limits workers’ ability to control their schedules and pace of work due to the unpredictable availability of tasks on these platforms. Despite the promise of flexibility, crowdworkers often have to be constantly available, which disrupts their ability to plan work and personal time effectively.

Key findings include:

- Impact on Schedule Control: Workers struggle to stick to planned work hours due to the unpredictable posting of tasks. This results in less actual work time and more time spent in unpaid ‘on call’ activities like waiting for new tasks.

- Impact on Work Pace: The on-demand nature of task availability forces workers into a state of constant readiness, which interferes with the natural pacing of work and break times. This can lead to increased stress and decreased job satisfaction.

The paper also discusses broader implications for the platform economy, suggesting that real temporal flexibility is often not realized for many workers in these environments. It calls for platform design changes to enhance real flexibility and improve working conditions for crowdworkers.

How did people respond to the disruption to work caused by the pandemic?

Our paper “The new normals of work: a framework for understanding responses to disruptions created by new futures of work” has just come out in Human-Computer Interaction Journal.

Open access to the paper is available here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07370024.2021.1982391

In the paper, we explore how people adapted to work during the pandemic and how we might understand people’s response to disruption in the new future of work. We highlight a number of issues, tools and strategies that people used in their work to support them while working remotely. For example, virtual commutes, having dedicated space, new scheduling techniques or staying connected with colleagues through virtual chats and async chats

Exploring these with the Genuis and Bronstein model of “new normal” we show 3 kinds of responses:

- waiting to return to old normal,

- finding a new normal and

- anticipating a new future of work.

These new normals of work help us to understand how we can help workers going forward.

We’d like to thank our reviewers for their feedback and our participants for helping develop our work within eworklife.co.uk and a special shoutout to @DilishaBP whose work with the new normal model inspired this work 😀 You can find their paper on Finding a “New Normal” for Men Experiencing Fertility Issues here: dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.114…

If you find this interesting you might also like our other papers on work during the pandemic:

- Disengaged From Planning During the Lockdown? An Interview Study in an Academic Setting Yoana Ahmetoglu; Duncan P. Brumby; Anna L. Cox (2021) IEEE Pervasive Computing

- Staying Active While Staying Home: The Use of Physical Activity Technologies During Life Disruptions Joseph W. Newbold, Anna Rudnicka and Anna Cox (2021) Frontiers in Digital Health

- Eworklife: Developing effective strategies for remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic A Rudnicka, JW Newbold, D Cook, ME Cecchinato, S Gould, AL Cox (2020) The New Future of Work Online Symposium

The first draft of this blogpost was written as a twitter thread by Joe Newbold and unrolled using ThreadReader

The great remote work experiment – what happens next?

Sam Wordley via Shutterstock

Daniel Merino, The Conversation and Gemma Ware, The Conversation

In this episode of The Conversation Weekly, four experts dissect the impact a year of working from home has had on employees and the companies they work for – and what a more hybrid future might look like. And we talk to a researcher who asked people to sit in bathtubs full of ice-cold water to find out why some of us are able to stand the cold better than others.

For many people who can do their job from home, the pandemic meant a sudden shift from office-based to remote working. But after a year of working from home, some company bosses really don’t want it to become the new normal. The chief executive of Goldman Sachs, David Solomon, called it an “aberration”, and Barclays chief executive Jes Staley said it wasn’t sustainable, because of how hard it is to maintain culture and collaboration with teams working remotely.

Meanwhile, others are fully embracing a remote work future. Twitter said its employees could work from home forever, and Spotify announced a “work from anywhere” policy. Other firms are starting to announce more hybrid policies, where people are expected to split their week between the home and the office: in March, BP told employees they would be expected to work from home two days a week.

In this episode, we talk to researchers who have been studying the shift to remote working during the pandemic about their findings. In France, Marie-Colombe Afota, assistant professor in leadership, IÉSEG School of Management in France, talks us through the initial results of a new study she did in late 2020 of 4,000 employees at a large French multinational. “The more employees felt that the organisation generally values being visible in the office, the more they felt expected to be constantly available while in remote work,” says Afota. “And, in turn, two months later, the less they felt productive and happy in remote work.”

A year of working from home has left some people close to burnout, according to Dave Cook, a PhD researcher in anthropology at University College London who has been interviewing people about their experiences of shifting to remote work during the pandemic. “Burnout and work-life balance is the forgotten public health emergency that’s emerging through throughout this lockdown,” he tells us. And he says that companies should start communicating with their staff now about what the future has in store: “So their employees can get on with planning the rest of their lives.”

For others, the shift to remote work has been a surprisingly good experience. Jean-Nicolas Reyt, an assistant professor at McGill University in Montreal, has been tracking the language that chief executives in North America used to talk about remote working in 2020. “What you see is that actually that misconception, that telework is just not as efficient as co-located work, has vanished for a lot of CEOs,” he tells us. “A lot of CEOs and a lot of employees are saying it was forced, but it’s actually pretty good.”

Ruchi Sinha, a senior lecturer in organisational behaviour and management at the University of South Australia, gives the view from Australia, where hybrid working is already becoming a reality, and where most invitations to a face-to-face meeting now come with a video link too. But Sinha says that opportunities to shift to a fully flexible way of working may be being missed, with companies implementing new policies as rigid as the old ones. “I don’t think we are spending enough time thinking about are we giving people choice to shape their jobs, to shape what they do,” she tells us.

In our second story, we find out that your genes influence how resistant you are to cold temperatures. To test this, scientists asked a group of men to sit in bathtubs full of icy water to measure their reaction – and how much they shivered. Victoria Wyckelsma, a postdoctoral research fellow in muscle physiology at the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, explains what they found and what it means.

And Sunanda Creagh from The Conversation in Australia gives us some recommended reading about the recent floods in Sydney.

Read more:

‘They lost our receipts three times’: how getting an insurance payout can be a full-time job

The Conversation Weekly is produced by Mend Mariwany and Gemma Ware, with sound design by Eloise Stevens. Our theme music is by Neeta Sarl. You can find us on Twitter @TC_Audio or on Instagram at theconversationdotcom. We’d love to hear what you think of the show too. You can email us on podcast@theconversation.com

A transcript of this episode is available here.

News clips in this episode are from CNN, CNBC News, CBC News, NBC News, Arirang News, World Economic Forum, Goldman Sachs, AlJazeera English, 7 News Australia, Sky News Australia,, Euronews, DW News and Jornal da Record.

You can listen to The Conversation Weekly via any of the apps listed above, our RSS feed, or find out how else to listen here.![]()

Daniel Merino, Assistant Editor: Science, Health, Environment; Co-Host: The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation and Gemma Ware, Editor and Co-Host, The Conversation Weekly Podcast, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media interview: ‘If you switch off, people think you’re lazy’: demands grow for a right to disconnect from work

Prof Anna L Cox is quoted in The Guardian’s article ‘If you switch off, people think you’re lazy’: demands grow for a right to disconnect from work

How the pandemic will shape the workplace trends of 2021

Elenabsl/Shutterstock

The economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in 1930 that the amount we work would gradually shrink to as little as 15 hours a week as technology made us more productive. Not only did this not happen, but we also began to spend extra time away from home due to commuting and suburban living patterns, which we often forget are recent historical inventions.

However, 2020 has changed all that. In my new history of remote work during COVID-19, I marvel at how much it has shaken up our lives and how much we took for granted. My research also points to a number of trends that will help shape working life in 2021.

Gene Daniels.

Over “in time for Christmas”

At the start of 2020 remote work was a gradually rising long-term trend. Only 12% of workers in the US worked remotely full time, 6% in the UK. Naturally the world was unprepared for mass remote work.

But COVID-19 instantly proved remote work was possible for many people. Workplace institutions and norms toppled like dominos. The office, in-person meetings and the daily commute fell first. Then the nine to five schedule, vacations and private home lives were threatened. Countries even started issuing remote work visas to encourage people to spend lockdown working in their territory.

As old norms vanished, a rapid procession of novel technologies marched uninvited into our homes. We had to master Zoom meeting etiquette, compassionate email practices, navigate surveillance, juggle caring responsibilities. The list goes on.

In the face of grim statistics – the UN predicted 195 million job losses – only the tone deaf complained about working from home. Nonetheless, COVID-19 created the biggest remote work experiment in human history.

In July, UK prime minister Boris Johnson – with Edwardian optimism – daydreamed a sense of normality would return “in time for Christmas”. Fast forward through summer to lockdown 2.0 and the fantasy of a 12-week experiment faded into sepia tinged memories. One interviewee joked: “I really thought we’d be back in the office by July, what fools we were!”

Are you disciplined?

Silicon Valley companies Google, Apple and Twitter were among the first to announce employees could work from home. Ahead of the curve, they were well practised. Predictably, they already had a fancy term for it: distributed working. In 2021 concepts such as distributed and hybrid working will proliferate.

Most were less prepared than Silicon Valley. In March, I published findings from a four-year research study tracking remote workers. I warned, to be a successful remote worker deep reserves of self-discipline were required, otherwise burnout followed.

We understand this now. But I spent the first lockdown patiently explaining to news outlets why working from home was so hard. When I suggested returning to the office might be considered a luxury – because it helped people structure their days – a news presenter laughed. For good or ill, conversations about disciplined routines will intensify in 2021.

Read more:

Remote working: the new normal for many, but it comes with hidden risks – new research

By May 2020 many reported experiencing Zoom fatigue. I naively predicted Zoom use would subside.

I’d have been right if we’d returned to the office. Instead necessity dictated we up our Zoom game – even if they were draining. Zoom simultaneously saved and ruined working from home, and it’s not going away anytime soon.

Michael D Edwards/Shutterstock

The commuting paradox

Remote workers, grateful to still have jobs, also reported a gnawing sense of survivors’ guilt. Overwork was one way of expressing this guilt. Many felt working extra hours might secure their job.

In April 2020, I joined other academics researching work-life balance on a project called eWorkLife. The research data revealed increases in working hours when it wasn’t obvious when the working day ended. Especially with no obvious signal to end the working day.

In my four-year remote study, I had noticed a strange pattern. Participants initially said “escaping the commute” was a key benefit of remote working. Yet months later these same workers started recreating mini commutes.

The eWorkLife project uncovered similar findings. People wanted to create “a clear division between work and home”. Study lead Prof Anna Cox urged people to do pretend commutes so they could maintain a work-life balance. In 2021 work-life balance must become recognised as a public health issue and the eWorkLife project is urging policymakers to act.

Khakimullin Aleksandr/Shutterstock

The right to disconnect

What’s happened to the time previously lost to commuting? Many are using it to catch up on admin and email. This taps into a worrying trend.

Pre-pandemic warnings about an encroaching 24/7 work culture were intensifying. Social scientists argued that contemporary workers were being turned into worker-smartphone hybrids. In 2016, French workers were even given the legal right to disconnect from work emails outside working hours.

A hopeful wish-list for 2021 includes continued increases in workplace activism and for companies and governments to reveal their remote working policies. Twitter and 17 other companies have already announced employees can work remotely indefinitely. At least 60% of US companies still haven’t shared their remote working policies with their employees. Remote workers tell me until bosses reveal their post-pandemic policies – planning for their future is impossible.

Read more:

Remote-work visas will shape the future of work, travel and citizenship

The late activist David Graeber described the failure to achieve Keynes’s 15-hour work week as a missed opportunity, “a scar across our collective soul”. COVID-19 may have started conversations about alternative futures where work and leisure are better balanced.

But it won’t come easily. And we will have to fight for it.![]()

Dave Cook, PhD Candidate in Anthropology, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Talk: Games for Academic Life

Prof Anna L Cox gives keynote speech “Games for

Academic Life” at GALA 2020, Games and Learning Alliance conference.

A copy of the slides is available for download.

Media interview: Sandy Gould in The Loop

Dr Sandy Gould talks about the results of a study that we presented at the Microsoft Research New Future of Work Symposium “The New Remote Working Age” in Bridgehead Communication’s ‘The Loop’

The Global Remote Work Revolution and the Future of Work

Dave Cook, who has been collaborating with us on the eWorkLife Remote Work study has published a chapter in The Business of Pandemics book: The Global Remote Work Revolution and the Future of Work.

Remote-work visas will shape the future of work, travel and citizenship

During lockdown, travel was not only a distant dream, it was unlawful. Some even predicted that how we travel would change forever. Those in power that broke travel bans caused scandals. The empty skies and hopes that climate change could be tackled were a silver lining, of sorts. COVID-19 has certainly made travel morally divisive.

Amid these anxieties, many countries eased lockdown restrictions at the exact time the summer holiday season traditionally began. Many avoided flying, opting for staycations, and in mid-August 2020, global flights were down 47% on the previous year. Even so, hundreds of thousands still holidayed abroad, only then to be caught out by sudden quarantine measures.

In mid-August for example, 160,000 British holiday makers were still in France when quarantine measures were imposed. On August 22, Croatia, Austria, and Trinidad and Tobago were added to the UK’s quarantine list, then Switzerland, Jamaica and the Czech Republic the week after – causing continued confusion and panic.

This insistence on travelling abroad, with ensuing rushes to race home, has prompted much tut-tutting. Some have predicted travel and tourism may cause winter lockdowns. Flight shaming is already a cultural sport in Sweden, and vacation shaming has even become a thing in the US.

Amid these moral panics, Barbados has reframed the conversation about travel by launching a “Barbados Welcome Stamp” which allows visitors to stay and work remotely for up to 12 months.

Prime Minister Mia Mottley explained the new visa has been prompted by COVID-19 making short-term visits difficult due to time-consuming testing and the potential for quarantine. But this isn’t a problem if you can visit for a few months and work through quarantine with the beach on your doorstep. This trend is rapidly spreading to other countries. Bermuda, Estonia and Georgia have all launched remote work-friendly visas.

I think these moves by smaller nations may change how we work and holiday forever. It could also change how many think about citizenship.

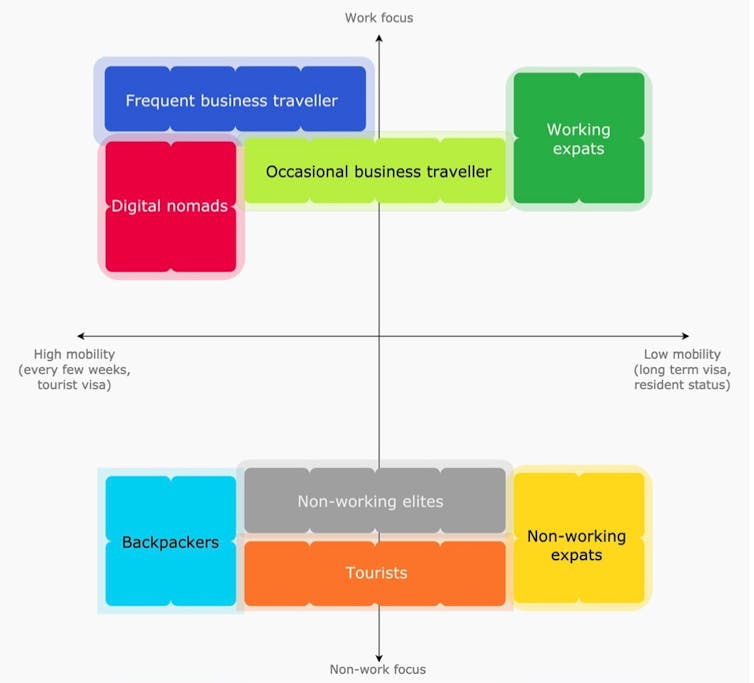

Digital nomads

This new take on visas and border controls may seem novel, but the idea of working remotely in paradise is not new. Digital nomads – often millennials engaged in mobile-friendly jobs such as e-commerce, copywriting and design – have been working in exotic destinations for the last decade. The mainstream press started covering them in the mid-2010s.

Fascinated by this, I started researching the digital nomad lifestyle five years ago – and haven’t stopped. In 2015, digital nomads were seen as a niche but rising trend. Then COVID-19 paused the dream. Digital nomad Marcus Dace was working in Bali when COVID-19 struck. His travel insurance was invalidated, and he’s now in a flat near Bristol wondering when he can travel.

Dace’s story is common. He told me: “At least 50% of the nomads I knew returned to their home countries because of CDC and Foreign Office guidance.” Now this new burst of visa and border policy announcements has pulled digital nomads back into the headlines.

So, will the lines between digital nomads and remote workers blur? COVID-19 might still be making international travel difficult. But remote work – the other foundation of digital nomadism – is now firmly in the mainstream. So much so that remote work is considered by many to be here to stay.

Before COVID-19, office workers were geographically tethered to their offices, and it was mainly business travellers and the lucky few digital nomads who were able to take their work with them and travel while working. Since the start of the pandemic, many digital nomads had to work in a single location, and office workers have become remote workers – giving them a glimpse of the digital nomad lifestyle.

© Dave Cook and Tony Simonovsky, Author provided

COVID-19 has upended other old certainties. Before the pandemic, digital nomads would tell me that they despised being thought of as tourists. This is perhaps unsurprising: tourism was viewed as an escape from work. And other established norms have toppled: homes became offices, city centres emptied, and workers looked to escape to the country.

Given this rate of change, it’s not such a leap of faith to accept tourist locations as remote work destinations.

A Japanese businessman predicted this

The idea of tourist destinations touting themselves as workplaces is not new. Japanese technologist Tsugio Makimoto predicted the digital nomad phenomenon in 1997, decades before millennials Instagrammed themselves working remotely in Bali. He prophesied that the rise of remote working would force nation states “to compete for citizens”, and that digital nomadism would prompt “declines in materialism and nationalism”.

Before COVID-19 – with populism and nationalism on the rise – Makimoto’s prophecy seemed outlandish. Yet COVID-19 has turned over-tourism into under-tourism. And with a growing list of countries launching schemes, it seems nations are starting to “compete” for remote workers as well as tourists.

The latest development is the Croatian government discussing a digital-nomad visa – further upping the stakes. The effects of these changes are hard to predict. Will local businesses benefit more from long-term visitors than from hordes of cruise ship visitors swarming in for a day? Or will an influx of remote workers create Airbnb hotspots, pricing locals out of popular destinations?

It’s down to employers

The real question is whether employers allow workers to switch country. It sounds far-fetched, but Google staff can already work remote until summer 2021. Twitter and 17 other companies have announced employees can work remotely indefinitely.

I’ve interviewed European workers in the UK during COVID-19 and some have been allowed to work remotely from home countries to be near family. At Microsoft’s The New Future of Work conference, it was clear that most major companies were mobilising task forces and would launch new flexible working policies in autumn 2020.

Countries like Barbados will surely be watching closely to see which companies could be the first to launch employment contracts allowing workers to move countries. If this happens, the unspoken social contract between employers and employees – that workers must stay in the same country – will be broken. Instead of booking a vacation, you might be soon booking a workcation.![]()

Dave Cook, PhD Researcher, Anthropology, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.