Academic Life in 2019

Today many of my colleagues are on strike. I’m not joining them today because I am on leave to attend the funeral of a university friend who died a few weeks ago in his mid-40s.

His sudden and unexpected death has shaken me. It’s frightened me more than other events this year – two of my fittest and healthiest friends had heart attacks. If these things can happen to them, they can happen to me. It has made me want to refocus my life and think harder about what is important. I don’t want to have regrets.

I spend most of my life at either 100 miles an hour or so exhausted that I can’t move – I literally had no option but to spend 2 hours yesterday napping on the sofa. I was completely shattered. This kind of life isn’t good for my mental or physical health. It’s not how I want to live. It makes me scared that I’ll be the next person in my friendship group to have a major health problem. And that will have serious consequences for my family.

Despite the fact that I’m on leave today, I have spent the morning doing work activities. The lines between work and non-work are very blurred. It’s really effortful to create and maintain the boundaries between them when there is so much to do.

Academic life is engaging and exciting and full of responsibility. I need to ensure my taught students get a good experience, can pass their assessments and receive useful feedback so they can improve their learning. I have PhD students to train and support as they learn to deal with the frequent rejections that come from reviewers. I have grants to write so that my post-docs have jobs – without funding they will be made redundant. I have made a commitment to try to make my institution a better place for everyone to work in my role as Vice Dean Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. And I have promised to help those in my academic community by reviewing papers and organising conferences and to foster links between universities and schools by being a school governor. All of these activities give me a sense of reward and accomplishment. I’ve made all these commitments because I think they’re important and want to keep them. In addition there are frequent requests for reference letters to support people getting new jobs or going for promotion. And from members of the media who want comments which could help the public understand and engage with science. And other things that I can’t even remember right now.

No wonder I am exhausted.

But I’m not alone. This week Mary Beard tweeted…..

“Can I ask academics of any level of seniority how many hours a week they reckon they work. My current estimate is over 100. I am a mug. But what is the norm in real life. ?” https://twitter.com/wmarybeard/status/1198351088832962560

Responses seem to fall into a few categories:

· Accusing her of lying: People find it hard to believe that can be telling the truth – who can work that number of hours?

· Shaming her for having privilege: People accusing her of perpetuating a culture of overwork and unnecessarily increasing the competitive culture within academia

· Sympathy and acceptance: People who recognise that they’re in a very similar position

UCL’s standard working week is 36.5 hours excluding meal breaks. Two of my colleagues shared the outcome of their attempts to track how many hours they’ve worked this year. By the end of August they had already worked their full annual allocation of hours. They work around 55hrs per week on average. So September to December they will work for free. Not standard weeks but still averaging around 55hrs per week. By the end of the year they will have worked an extra 50% above their contracted hours. I think this is common. It’s very difficult to say no to the endless requests or to deal with the guilt of letting someone down. Instead we put our own mental and physical health at risk, we do the work of 1.5 people, and our employers continue to take advantage of us.

Last year, in 2018, I went on strike along with many of my colleagues. As a result I lost a substantial amount of pay. Whilst this meant that some of lectures were cancelled and students were impacted, the reality is that I worked throughout the strike period. I worked a standard week as well as spending time on the picket line and on a march.

Some will say that my actions undermined the strike action by minimising it’s impact. But my actions were necessary to support my own mental health. I couldn’t deal with the stress of a huge pile of work that would all have to be done in the weeks after the strike. The reality of academia is that if you are away on leave for any reason, no one covers your job for you. You just have to work harder and longer afterwards.

During this strike period I don’t have any teaching duties. Even if i did, going on strike seems like an ineffective form of protest – it might hurt our students in the short term but it leaves untouched those who have the authority to improve the situation for all university staff. I’m not sure whether I’m going to strike in the coming days. This is certainly a time for reflection about what matters.

Sabbatical thoughts on productivity, the planning fallacy and recovery – month 2 of the commitment calendar

Following my previous post on the commitment calendar I was asked to share the spreadsheet that I am using to help me get a sense of what I have committed to do each month. The link to that is here.

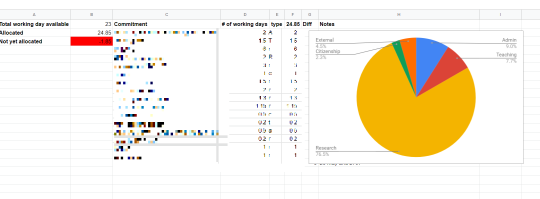

This is now the second month of using it. I sat down on the morning of the first working day of the month to plan out what I was going to get done, and when that was going to happen. I have found it easiest to use half days as the smallest unit. Coming up with the list of stuff that has to be included takes a few steps:

1) Standard predictable things like scheduling some time each week to review my to-do list, plan what needs to be done, update this spreadsheet, schedule stuff in my calendar, etc. I’m scheduling half a day a week for this. The first one of these in the month is used for planning the rest of the month but it’s not clear what the rest of these slots will be used for yet. Sure, I’ll need a bit of time every week to check my to-do list etc but I hope I won’t need half a day a week. This will allow for a little slack in the schedule. I am also being explicit that I need time to do email. I am blocking out half a day a week to get my inbox to zero and respond to messages and do small admin tasks.

2) Then there is the stuff that will vary depending on what your roles are as an academic. I’m including supervision time: how much time you devote to this will depend on how many students you have but need to cover all the time spent on face to face contact, reading and commenting on drafts, etc. I’ve also added in time for teaching (to cover preparation, contact time and marking) and time for citizenship/admin roles such as sitting on committees and leading programmes.

3) Stuff that’s happening this month only – this will be things like attending a conference or taking some holiday.

The next thing that happened was I realised just how over-committed I was for the month. As a result I decided that there were some things that weren’t going to happen this month. Having to make hard decisions and accepting that I can’t get everything done that I might like to has made it easier to say no to other requests that have come in over the past week.

I have found it useful to schedule half day slots in my diary that relate directly to the commitments so i know when I am going to get each of these things done. This is helping me see what can get done in half a day (and what can’t!). For example, is half a day enough time to read a paper and write a review for it? I am hoping that this provides me with more insight into how long it takes you to do different things so it is easier to plan with more accuracy (though it’s well known that we find it very difficult to avoid being overconfident about what we can achieve in a given time https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planning_fallacy ) Even engaging in this planning task has helped me realise that there are some things that I can’t do as early as I would like.

So far this week my 3 working days have been MUCH longer than I had wanted or planned for them to be. This suggests that I’m still overestimating what can be done in a given amount of time. It has also meant that today (Thursday) I’ve been much less productive than I wanted to be and have struggled to motivate myself to do the things I had planned to do. Hopefully tomorrow I will have recovered enough to have the energy to catch up with the things on today’s list that haven’t been finished.

Reflections on a writing retreat

One of the to-dos on my sabbatical bucket list is to submit a particular grant proposal I have been slowly working on with two colleagues. We all work at different institutions and it seemed like a great idea to find an opportunity to get our ideas down on paper – preferably whilst we were co-located and away from our usual places of work.

Earlier this year I discovered that Maureen Michael from Room For Writing was leading a writing retreat to be held in May. I asked my two colleagues if they would be interested in going. I thought the structure provided by the retreat would give us the best chance of getting it done as we would be forced not to spend the whole day talking! A few weeks later we were all booked to go.

We scheduled a skype call a couple of weeks ahead of the retreat to refresh our memories and make sure that we still agreed on what we wanted to do. Our planning included breaking down the writing of the proposal into discrete chunks and scheduling them each for a particular time slot.

The day of the retreat arrived. Two of us arrived in Glasgow early and spent the morning talking about the ideas we had for the project.

By lunchtime the three of us were together and some more chat ensued. At 3pm we were met by a taxi and 3 other retreaters for the journey to the Black Bull Hotel in Gartmore, about an hour outside of Glasgow.

After tea and coffee, and introductions, twelve people sat down to start a 5 minute free writing task in which we had to write in full sentences (but without editing) and answer 2 questions: for the writing task we were going to focus on, what had we already written for it and what did we want to achieve by the end of day 3, the end of day 2, and the end of the coming 60 minute session?

We then formed pairs and talked for 5 minutes each about what we were going to write. We were instructed to ask questions to help the other person to articulate a very clear goal. Sixty minutes later we had completed our first writing slot and we had written three work-packages. We were rewarded with a fantastic three course dinner.

The Black Bull Hotel in Gartmore is a really charming place, with humorous staff and an amazing cook. Breakfast consisted of fruit, cereal, porridge, and everything you would expect from a full Scottish breakfast. Elevenses were freshly baked scones or gorgeous fluffy pancakes served with jam, cream and maple syrup. Lunch on day 2 was salad and jacket potatoes with tuna and prawns. And on day 3 was fajitas and salad and quiche. There was also afternoon tea on all three days that included things like this delicious and beautiful “cake object”.

The retreat was structured to include 8 writing sessions that each lasted 60-90 minutes. The morning and afternoon breaks lasted 30 minutes and lunchtime was 90 minutes that included strong encouragement to take a walk or go for a run.

Over the course of the three days we completed 10.5 hours of focused writing, went on 5 walks, and were very well looked after. I have come away from this experience feeling incredibly productive (and consequently a bit tired!) but also cared for, and reminded of a slower way of working. Maureen is very skilled at creating an atmosphere in which being focused and productive feels easy. She also carefully guides you through re-evaluating your goals so that, at the end of the process, you focus on your successes and achievements and have insight into how to set realistic goals for writing.

So how did it go? We we wrote a grant proposal! We have about 9000 new words that have been revised by each of us several times so they’re of reasonably high quality. To be completely honest we have achieved more than I had dared to believe was possible in the time.

We used the breaks to relax but also to chat about progress and to share ideas about how to develop the ideas in our proposal. That meant that, compared to other participants at the retreat, we probably “worked” through the breaks rather than using them entirely for recovery.

That said, the process didn’t feel frantic or like we were under pressure but felt relaxed and was quite unlike my usual working days. I don’t usually take breaks when I’m working and sometime even miss out on lunch. I know it’s not good for me but somewhere between being immersed in my work and under pressure to get lots of things done it’s been an easy habit to develop. I’m going to try to change that and see if I can schedule substantial breaks in my day. I’m interested to see how that impacts my work and wellbeing (though perhaps I will eat less cake than when in Gartmore!).

If you’re interested to know more about structured writing retreats like the one I attended then you can read Rowena Murray & Mary Newton’s paper here.

You can find more information about Room For Writing on their website.

Creating my commitment calendar & getting to grips with the to-do list

I’m forever on the lookout for ways to help me better manage my to-do list. I hate the feeling of being behind and constantly missing deadlines. As I’m currently on a 3 month sabbatical and now that my responsibilities for CHI2019 are over now seems like a good time to review what i do and try to improve things for the future.

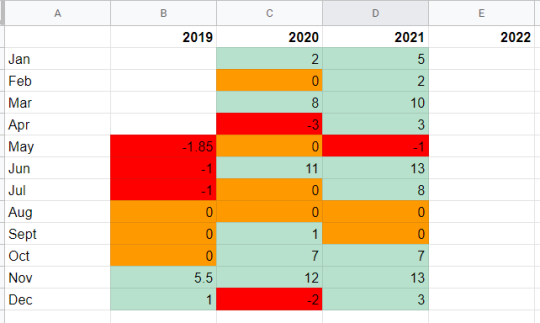

I was recently reminded of Amy Ko’s blogpost in which she describes keeping a “commitment calendar” that covers each month into the next 2 years. I remember when i first heard her talk about it on Geraldine Fitzpatrick’s podcast and wondering how on earth she managed it – it seemed like a difficult thing to do. I just couldn’t work out how you would know what you were going to be doing that far ahead. But something made me think that this might be worth trying to i sat down with my notebook and devoted 2 pages to mapping out the next 2 years.

It was actually much easier than i expected it to be. I tend to take holiday with predictable regularity dictated by school holidays – so that was the first thing i put in. And then the conferences that i usually attend also tend to follow a predictable pattern so I added those. I could then predict when i would most likely be working on the papers for those conferences, when i would have teaching and marking to do, and when my PhD students would need feedback on their upgrade reports and final thesis drafts. I’ve also got a bunch of other things already in my calendar – talks i’ve committed to giving, workshops I’m planning on attending, etc.

What was immediately visible was that I already know things that I’m going to be doing in 2 years time and which month those commitments are going to fall in. I could also see that the next 6 months look really busy! But just how busy?

I set about counting how many working days there were in each month and adding this information to the calendar. And then i started estimating how many days each commitment was going to take up. Now it was really clear that I have over-committed myself!

And then i remembered another thing I needed to add into this month! It was clear that paper commitment calendar just wasn’t going to cut-it. As more and more things that I have committed to come to mind I was going to very quickly run out of space on the sheets in my notebook. So I set about transferring it all into a spreadsheet.

And because I love a good pie chart I also worked out what percentage of my time I was spending on research, teaching, institutional citizenship (service) and external/knowledge exchange.

Next I created an overview sheet…..

…and had it automatically colour code each month as red if I am over-committed, amber if I have no capacity to take on any more, and green if there are work days still available to get work done. I was surprised to find that the month I got to the CHI conference is routinely full, as is December.

Engaging in this exercise has given me a whole new perspective on my workload. It now seems really obvious why I struggle to get things done and always feel like I’m behind. If I hadn’t done this I would have thought that October 2019 was pretty empty and that I could easily say yes to a whole host of new things. Now, when I receive a request to do something (examine a thesis, review a paper, join in on a grant with a short deadline, etc) I check the spreadsheet and actually think about how much work will be involved, and whether or not i have time to do it. If I have got time then I add it to the spreadsheet. If I haven’t, I say no. Given that i have so few “spare” days left this calendar year, I’m going to be very picky about what I say yes to using them for.

Edit: following a few requests i made a copy of my spreadsheet available if you want to try it out. Copy and paste it and then you can edit it and put in your own stuff. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1jzfJP17AboKEKcqM9if-2fPobnHnD3bvl6E96cd95P4/edit?usp=sharing

Leadership: the importance of talking about failure

Reblogged from https://martaelizabethcecchinato.wordpress.com/2016/06/20/leadership-the-importance-of-talking-about-failure/

There was a CV going around social media and the press posted by a tired academic who wanted to expose just how much our culture is based on success and competition. It was eye opening… As a fairly young academic myself, it was encouraging to read and know that others have bad days too. About a month ago, I was talking to a colleague I look up to and found out that behind her successes there were rejected papers. I had no idea. In academia, it is common to celebrate successes, and perhaps brag about them too, but it is also common to complain about reviewer 2, the biased editor, or the tardiness with which a paper is handled. There’s a good summary of typical academics and how to handle them here. Being a woman in STEM it can be considered even more important to just show off the best results and just how successful one is, to compete against gender bias. So when I attended the event “Women in Leadership” organised by UCL PALS Athena Swan I was expecting an empowering talk on how to stand up against men and show off our best traits. I have never been so wrong.

The talk was given by Harriet Minter, founder and editor of the Guardian column ‘Women in Leadership’. She started off by telling her story of how she became a leader, which was not only filled with all the ingredients of a woman in the workplace – self-doubt, wanting to fix everything, imposter syndrome – but covered also a good handful of failures and knock downs. More importantly, for every failure or road bump, she presented a series of lessons learnt, showing off what a great leader she is.

There were other two refreshing elements in her talk: 1.First of all, most of the talks or articles for women in the workplace, focus on the idea that we need to learn to say ‘no’ in order to set boundaries, protect our time, and prevent us from our worst enemy: “the red cross nurse syndrome” (that’s what we call in Italian the tendency that women have to fix everything and take care of others in spite of their own health). Harriet instead reminded us that ‘no’ is not always the answer, and that new opportunities, exciting projects, and adventures only come if you don’t say ‘no’ all the time, but remember to say ‘yes’. 2.Secondly, although the title of the event was “Women in Leadership” and she referred to several role models throughout, the lessons are for everyone. I counted three men in the packed room of about 50 people, which is the highest male attendance I’ve ever seen at such events. More than focusing on empowering women alone, her talk was aimed at changing the overall mentality of women in the workplace, and therefore aiming to both men and women.

So what were some of the lessons learnt?

PROCEED UNTIL APPREHENDED

No matter the amount of failure, you can only succeed if you don’t give up. So whenever you are stuck, have a problem, or have an idea you don’t know how to concretise: 1.Scale it down. Starting off with a grand project can be frightening for you, or even those that are supposed to invest in you. By scaling it down, you have an achievable starting point to build on. 2.Find an ally, to be reassured and have a boost in confidence, especially when things get hard. 3.Just start. Although this sounds a lot like the best marketing slogan, she and Nike have a point: start small and simple. Things will never change unless you do something about it.

WE ARE ALL HEROS WITH A QUEST

She then compared her story with that of any hero’s narrative. Whenever you watch a Disney or Marvel movie, or any other film/book/comic that has a hero, there are always five elements of the story. Filmmakers, theatre producers, and storytellers study this at school, like my friend Elisa who had first pointed out these five elements to me six years ago, but we just tend to think that they belong to the fictional life, while instead this happens to all of us: 1.There is a hero with a quest and a bunch of skills in a backpack. 2.The hero starts his/her journey so excited and filled with hope, that he/she suddenly missed the bit pothole in front of him/her, and falls down. 3.While the hero is stuck down there, in order to get back on track to his quest, he/she reaches in the backpack. While the skills he/she finds in there are not necessarily the right ones to get him/her out, it’s how he/she uses them that will get him/her out [*will get back to this point later] 4.As the hero climbs out of the pothole, a mystery stranger arrives and puts him/her back on the path 5.The hero finally succeeds in his/her quest.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ENDURANCE AND RESILIENCE

This is the point of the story where the best advice she was ever given, Proceed until apprehended, ties in with the hero’s narrative. When the hero is in the pothole, he/she can keep trying, keep going, just like a runner can reach the finish line if he/she pursues long enough. But when they get out, they might not have any energy left to notice the stranger or proceed on the path. This is where resilience comes in. Resilience is the ability to still stand and walk away when you reach the finish line, or you climb out of the dungeon and proceed on your path to success. Even if we don’t have the right skills for the task, it’s up to us to adapt the skills that we do have, to make things work for us. By learning from past failures and falls, we can practice and learn our resilience skills.

FIND YOUR TEAM

Finally, the last bit of advice comes from her encounter with Sheryl Sandberg, who performed the equivalent productivity sprint of a month’s work in just three hours, whilst visiting The Guardian. If behind every successful man they say there is a strong woman, behind every successful woman there is a team. In Sheryl’s case, it was made up of people who would help her keep to time and take care of menial tasks. In our case, this team is our support network that can help us in rough times, and on whom we can rely on for the skills we lack. We just have to remember to play in other people’s teams too…

Going back to the beginning of this post, the importance of talking about failure lies in the ability to roll up your sleeves, stand up again and learn from it. In my giant OneNote notebook called unimaginatively ‘PhD’, I now have a section called “failures”, where I write all the things that go wrong and what I can learn from them, as well as keep track of my own hero journey.

An argument for more Interaction Science to plug “The Big Hole in HCI Research”

The latest edition of the ACM Interactions magazine http://interactions.acm.org/ includes an article by Vassilis Kostakos (@vkostakos http://www.ee.oulu.fi/~vassilis/ ) titled The Big Hole in HCI Research in which he comments on an article that he and colleagues published at CHI2014. Their paper CHI 1994–2013: Mapping two decades of intellectual progress through co-word analysis. describes the research that has been published at the ACM CHI conference over the previous twenty years. Through co-word analysis, they demonstrate a lack of motor themes in the research that is published at CHI. “Motor themes are the heart and soul of a discipline, its main topics or schools of thought. Surprisingly, we found that, unlike other disciplines, CHI has consistently lacked motor themes.” Kostakos argues that without motor themes one has to wonder whether CHI is a scientific conference at all. He echoes the points we have made previously about the dangers of focusing on implications for design, rather than valuing implications for theory.

Vassilis Kostakos. 2015. The big hole in HCI research. interactions 22, 2 (February 2015), 48-51. DOI=10.1145/2729103 http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2729103

Liu, Y., Goncalves, J., Ferreira, D., Xiao, B., et al. CHI 1994–2013: Mapping two decades of intellectual progress through co-word analysis. Proc. CHI 2014. ACM, New York, 2014, 3553–3562.

From zero to submission

Over the past few days there have been a whole bunch of interesting tweets relating to tricks that help people write better. Many of these have the #GetYourManuscriptOut hashtag that was set up by Raul Pacheco-Vega in his blogpost about the problems with finishing off papers http://www.raulpacheco.org/2014/07/getyourmanuscriptout-or-how-to-fight-procrastination-in-academic-writing-through-crowdsourcing/.

I guess all this attention on academic writing is because there’s a lot of writing going on at this time of year: many PhD students are currently finishing up their theses, as are many MSc students, academics are trying to get their paper submitted and those of us working in HCI are already focused on the CHI deadline on the 22nd September. As a result, I’ve spent most of today reading drafts and making comments on them, and pointing my students to various online resources that provide useful hints and tips about reverse-outlining http://explorationsofstyle.com/2014/06/25/reverse-outlines-from-the-archives/ and how to write good paragraphs https://medium.com/advice-and-help-in-authoring-a-phd-or-non-fiction/how-to-write-paragraphs-80781e2f3054.

So what are the secrets of writing a good paper? Rachel Cayley writes about the importance of extensive revision of a manuscript http://explorationsofstyle.com/2014/06/11/committing-to-extensive-revision-from-the-archives/. But how much revision is enough? How many drafts does it take to write a paper that’s good enough to be submitted? I discussed exactly this with one of my post-docs this summer. We’d made a rather last minute decision to submit a paper to a conference and had just one week until the deadline. In that week the paper went from verson1 to version12. After we’d submitted she asked me “Is it normal to go through that many revisions?” My immediate response was “Yes – of course!” but it prompted me to take a quick look through my folders to see how many revisions my papers usually go through before submission. Very quickly it became obvious that my papers tend to go through at least 10 versions before submission, and those that get accepted have (perhaps unsurprisingly) often had even more . It turns out that in this case 12 was enough and our paper was accepted. Of course we hadn’t been writing it all from scratch. We had various files which contained the method and analysis, and we’d spent many hours talking about the results. What we did do in that week though was quickly identify a narrative for the paper, write up the story, and iterate over the details of how best to present the findings. So, if you have done a lot of the thinking already, then in a week of concentrated effort you can iterate enough to get a paper from zero to submission.

I was surprised today by another colleague when I sat down to read version 1 of the paper we had decided to write for CHI2015. The reason I was surprised is because although it was version 1 it was so polished. It was so good it even prompted me to write to her asking how many versions it had really gone through before she sent it to me. “Just the one” she said! This isn’t the whole truth though as like the paper I wrote about above, we’d already done a lot of work on this one before she wrote the first word. We had written a fantasy abstract (an abstract for a paper that you’ve not even done the research for yet) back in January, and then after doing the study, we’d written an abstract for a talk (in May), and written and given the presentation (in July and August) so actually writing the first version of the paper was easy. The draft of the paper was started just two weeks ago with a file of notes that outline the structure of the paper, the literature that needs to be included, and the main contribution. It took just a week to write. My co-author wrote “I think a an awful lot of thinking has gone into this paper before I sat down to write it – we’ve spoken many times. […] So we’ve had a head start with this one and I’m glad we didn’t need 14 iterations to get it ready…”.

But not all papers can be written so quickly. Another paper I’m currently working on for CHI2015 is currently on version 9. We’ve already done a lot of iteration on it. Version1 was created in mid June and mainly consisted of cutting and pasting text that had already been written elsewhere into the correct format. There it sat for two weeks before more work was done on it. Through versions 2 to 6 the story changed, the paper got chopped from full 10 page paper to a short 4 page note and then back up again to a 10 page paper. During this process we changed our minds about exactly which studies were going to be included but by mid August we had settled on the story. The next two weeks saw versions 7 and 8 in which we refined the write up of the details of the studies, and worked on making the story flow. There’ll be another version or two before the deadline I’m sure. It’s clearly taken a lot longer than a week to write this one. A big part of that reason is because doing the writing has been part of the process of thinking about what our results mean. (See http://explorationsofstyle.com/2014/06/04/using-writing-to-clarify-your-own-thinking-from-the-archives/ for Rachel Cayley’s blog post about using writing to clarify your thinking.)

Having a deadline is always a good way to focus the mind and find the motivation to get something down on paper. So with the CHI deadline now three weeks away, is there enough time to get a paper together if you haven’t already got to version 8?

I’ve got one that reached version 6 today but we’ve had to strip out all the text and engage in some reverse outlining to try to identify one clear narrative for the paper. It’s been a painful day as a result but I’m still hopeful that we can craft it into a good paper before the deadline – there’s still a way to go but it seemed like we made a lot of progress today. With 3 weeks until the deadline I think this one stands a good chance. I’m even tempted to start another one – a paper I’ve been meaning to start for a year. With all the thinking that’s gone into it already perhaps it would only take a week to get into shape? The concrete deadline might be enough to make me put finger to keyboard.

And then there’s another that we’re really excited about but we’re not even half way through the data collection! If all goes to plan we’ll have finished running the study next week. It’s still tempting to think we might be able to do that one too. In my more rational moments it’s obvious that this will be hard to pull off. We won’t be able to write a polished draft in just a week as we haven’t had the luxury of months of thinking about the results and how best to communicate them. Nor will there be time for 10 to 12 versions of the paper to help us craft that story. Perhaps we should line this one up for September 2015?

The gamer in your life isn’t ignoring you, they’re blind to your presence

By Charlene Jennett, University College London and Anna L Cox, University College London

It’s irritating when you try to talk to someone playing a videogame. You tell them dinner is ready and they completely ignore you. Their eyes are glued to the screen, their fingers frantically pushing buttons. We find it rude and it has led to many an argument in the family home.

But research suggests that your children, partner or parent may not be simply ignoring you when they’re plugged in to World of Warcraft – they may be experiencing something called “inattentional blindness.”. This is when a person chooses to focus on one thing and as a result they are blind to everything else around them.

Psychologists say that our lives would be pretty chaotic if we didn’t selectively attend to things in our environment in this way. Every noise, every sight, every smell, would distract us from our goals. We would simply feel overwhelmed with incoming information and we wouldn’t be able to get anything done.

This is, in fact, a common experience of people who are diagnosed with attention deficit disorder. They feel overwhelmed because they are unable to focus their attention. People selectively attend to some things over others all the time to avoid this feeling. It’s a natural process.

But there are some activities that absorb your attention more than others. When sports players or musicians feel extremely focused on what they are doing, they might say they are “in the zone” or “in full flow”. Videogame players describe themselves as feeling “immersed” when they’re focusing. They are fully engaged in a new reality, as though submerged in water.

In our research at the UCL Interaction Centre, we have been investigating immersion for several years now, following on from studies on inattentional blindness carried out by psychologists in the 1950s and 1960s. We ask our participants to focus on one source of information while ignoring others. But where older studies had participants staring at screens or listening to sounds, we asked ours to play a video game.

In one study we asked participants to play a driving game until they were told to stop but we didn’t tell them how they would be told. Part way through the game, a small pop-up box appeared on the bottom right of the screen saying “End of experiment – click here.” Participants who performed well in the game were slower to click on the pop-up box. These were the players who rated themselves as highly immersed in our immersive experience questionnaire.

In another study we asked participants to play a spaceship game. They were told that several distracting sounds would be broadcast into the room but that they should ignore them and continue playing. Some of the sounds related to the game, such as a voice saying “space games are boring” while others were person-relevant, such as a voice saying “London is boring”. Others, such as a voice saying “collecting stamps is boring”, were simply irrelevant. At the end of the study, participants were asked to remember as many of the distracting sounds as possible. We found that participants who performed well in the game recalled fewer auditory distracters, particularly the irrelevant ones.

Our findings share quite a few similarities with traditional psychology experiments. People are less aware of visual distractions when they are highly focused on a videogame. They are less aware of auditory distractions too, with only the most relevant breaking through to their conscious attention.

Feedback and immersion

There is another a key difference between our work and those of traditional psychology experiments because unlike watching a screen, you get feedback when you play a videogame. We found that a person’s immersive experience and the extent to which they were less aware of their distracters is related to the feedback they received. Positive feedback and positive perceptions of performance are essential for keeping a person’s attention during gaming.

But even when an indicator of performance is clearly unrelated to their true performance, players are unable to prevent themselves from interpreting it as meaningful. In another version of our spaceship experiment, we rigged the game so that no matter how well the player controlled the spaceship, they would either score really well or score really badly. Despite it being obviously rigged we found the same results. Participants who scored high in the game rated themselves as more immersed and recalled fewer auditory distractions. What seems to be important for immersion then is not that players actually perform well, but that they are able to perceive themselves as performing well.

These results reveal the powerful impact that feedback has on people’s immersive experiences and their motivation to continue with an activity. Receiving regular feedback that you are doing well is pleasurable. It might even be viewed as addictive in some ways, as it motivates the player to keep coming back for more.

This in part helps us explain why the gamer in your life ignores you when you tell them it’s dinnertime. Game designers have clocked that providing feedback as part of the game encourages us to keep on playing. This same feedback encourages inattentional blindness in the player. And given that children are more prone to inattentional blindness than adults it’s a wonder that they hear anything you say.

Charlene Jennett was supported by an EPSRC DTA studentship.

Anna L Cox receives funding from the EPSRC and NIHR.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rough day at work? Call of Duty can help you recover

By Emily Collins, University College London and Anna L Cox, University College London

Videogames have a had a particularly bad rap lately, not least after a UK coroner suggested a link between Call of Duty and teenage suicide. But recent evidence suggests that gaming can be good for us and, in particular, can help us unwind after a stressful day at work.

Many of us spend much of our working days immersed in technology. A smartphone or tablet comes with many advantages, such as flexible working, but the spread of work-based technology can add to stress too. Many people complain about the constant pressure to reply to e-mails as soon as they are received, even if that’s at 10 o’clock at night.

And even if we do switch off from work, technology is often at the centre of our home life. Watching a favourite show, keeping up to date with social media or reading online blogs are a vital component of many people’s evening activities. And while videogames were once seen as the preserve of teenagers, they have grown exponentially in popularity in recent years, largely because players no longer need a specialist console to enjoy them.

Roughly 1 out of every 4 UK adults, across ages and genders, now plays some kind of digital game at least once a week. Despite this rising popularity, digital games rarely make headlines for anything positive. Before the most recent controversy about suicide, they have been blamed for a variety of negative effects, including causing Attention Deficit Disorder encouraging acts of violence and antisocial behaviour. At the very least, they are perceived to be a bit of a waste of time, with no real, external value.

But our recent evidence suggests that not only can digital games be good for you, they may also be beneficial for your work life. Post-work recovery is a vital part of feeling prepared for the next day because it’s when you replenish the mental resources you used up during the daily grind. And it’s beginning to look like the type of activity you do during this period is important too.

Activities such as playing team sports and socialising have been found to benefit recovery but for many, this requires dedication, time and resources that simply aren’t available. So turning to activities that can be performed for brief periods of time in any location could be an ideal solution. This is exactly where digital games fit in.

Unwinding online

Our work has built on previous studies that found that those who play digital games are better recovered than those who don’t. We were interested in whether the type of game is important; the experience of playing casual games such as 2048 is likely to be very different to that of playing Call of Duty, for example. We asked participants to estimate how much time they spent playing a variety of genres of digital games in a week and then got them to complete a questionnaire to assess how much interference they experienced from work while at home and how well they recovered after gaming. They were also asked about the social support they receive from others, both on and offline.

Those who played digital games were more recovered and experienced less work-home interference than those who didn’t. And the more time people spent playing, the more recovered they felt. First-person shooter games were particularly beneficial.

While no one genre helped with every aspect of recovery, many were good for one or another. Massive multiplayer online games, which generally involve completing challenges of increasing difficulty, were good for giving players a sense of mastery. Action games, on the other hand, were related to relaxation.

We also found that out of those who claimed to have formed relationships as a result of the digital games they played, the extent of recovery was influenced by the amount of social support they had online. This suggests that digital games are effective in helping with recovery from work at least in part because they provide an opportunity to socialise.

This particular study can’t establish conclusively that the games the participants played were directly responsible for the improved recovery. It may just be that those who play digital games may simply have more time available to recover. But the findings do go some way to suggest that this causal link is possible. We are currently in the process of running more controlled studies, testing whether digital games directly improve recovery, and if so, whether the kind of game or level of immersion are important factors.

Emily Collins receives funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

Anna L Cox receives funding from the EPSRC and NIHR.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Speed reading apps are great for snippets but not sonnets

By Anna L Cox, University College London and Duncan Brumby, University College London

A new app is about to come on the market with promises to dramatically increase the speed at which you read. Spritz is a text streaming technology that allows you to read a sentence, one word at a time. Each word is shown for only a brief flash, in the same place on a screen, before the next appears.

Up to 1,000 words can be shown every minute, which would allow you to race through an entire novel in just 90 minutes. This could revolutionise the way we read, particularly on small-screen devices, such as smartphones and smartwatches.

How it works

When we read, our eyes normally make a series of brief pauses to extract information before moving on. These are referred to as eye movement fixations and saccades. It is only during fixations that the eye processes what is before it.

Spritz allows you to read faster by presenting words in the same place on the screen. This means that the eye can remain in the same spot and does not have to waste time making lengthy saccades to get to the next word.

When we read we have to recognise words. Spritz supports this by focusing our attention on the most informative part of a word so that we recognise it quickly – the word’s optimal recognition position. This is done by highlighting the letter that should be fixated in a different colour to the rest. Doing this grabs our attention and makes us fixate at that point.

Spritz also takes into account some of the factors that explain why we don’t fixate on each word for the same length of time. Rather than reading each letter in a word, our visual system is able to process common words as whole units, using the context of the text and the overall shape of the word as clues to aid recognition. This means that words that are very similar to each other in shape, like “bed” and “fed”, will require more time to process than words that are more distinct, like “decide”. Spritz therefore slows down when displaying very short words and speeds up for words that are four to seven letters long.

Reading or skimming?

Reading is more than just moving your eyes across a page. It is a cognitive activity. Our brain is busy processing the meaning of the words that have been read. For demanding content or tasks, this cognitive processing can take time. We naturally compensate for this by lingering on some words for longer than others to give our brains time to process the meaning of what we are reading.

The spritz website hints that some in-house testing has been done and claims people are able to perform well when tested for their comprehension and recall of a text that they have just “spritzed”.

But there’s a potential problem with treating all words equally and pushing everything through a high-speed funnel. Experiments using Rapid Serial Visual Presentation (RSVP), participants have demonstrated attentional blink. They were more likely to miss something important because their attention is occupied by something else that they had just experienced. For example, if you’ve just read an emotionally charged word such as “coffin” or “murder”, you’re more likely to miss something important if it occurs very soon afterwards.

The current system doesn’t appear to offer any deeper adaption to the content that is being presented. It doesn’t slow down if a main character dies suddenly, or a complex idea is presented in a sentence. This is not so surprising as this would be an extremely difficult technological problem to solve.

Spritz does slow down at the end of sentences to provide the reader with a little extra time to process the sentence that has just been read. But this might not be sufficient. In fact, readers frequently re-read sections of text when it did not make complete sense on the first pass –- something that is not possible with this system.

Spritz users might find themselves missing important information that they would have caught with regular reading as a result.

So while this technology could open up fantastic opportunities for reading small snippets of text, such as a tweet, on a very small screen, there’s probably some way to go in the development of the technology before you’d want to read War and Peace on a smart watch.

Anna L Cox receives funding from the EPSRC.

Duncan Brumby University College London. He receives funding from the EPSRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.